FICHES INFO > VOUS PERFECTIONNER

Prévention des accidents de désaturation (ADD)

Le texte ci-dessous est extrait du livre Plongée Plaisir 4.

Pour des informations plus détaillées, nous vous invitons à lire les livres Plongée Plaisir et en particulier le livre Plongée Plaisir 4.

Les études et évaluations sur les ADD montrent un risque relativement faible, de l’ordre de 1 à 5 pour 10 000 avec une rémission possible, après traitement hyperbare, dans la plupart des cas. Si la rapidité de l’alerte et de l’intervention (oxygène, évacuation vers un caisson hyperbare) est cruciale, la prévention est essentielle.

Voir également : Déshydratation et plongée, diurèse d’immersion.

La formation de bulles au cours de la désaturation, qui débute à chaque remontée, fait intervenir :

- La quantité réelle de gaz inerte (azote) dissous au cours de la plongée, qui dépend du débit cardiaque (consommation d’air). Elle est spécifique à chaque individu et dépend des conditions de plongée. Effort, froid, essoufflement, stress sont des facteurs d’augmentation de cette quantité d’azote dissous, au risque de se situer en dehors des hypothèses du modèle de votre ordinateur.

- La préexistence de poches de germes gazeux ou micro-noyaux gazeux qui favorisent l’apparition puis le grossissement et la libération de bulles.

Durant la désaturation, la quantité de gaz réellement dissoute et le nombre de poches de germes gazeux dictent le potentiel de création de bulles. Les conditions de la désaturation (vitesse de remontée, paliers, profil, comportement, gaz respiré à la remontée et/ou au palier) et des facteurs individuels (certaines personnes sont plus « bulleuses » que d’autres) vont induire le niveau de bulles réel.

Celles-ci ne causent pas d’accident lorsqu’elles restent de petite taille et peu nombreuses : elles sont éliminées par le filtre pulmonaire à l’expiration. On parle de « bulles silencieuses ».

Mais ces microbulles peuvent aussi :

- grossir lors de la remontée ou s’associer entre elles pour former des emboles ou des manchons gazeux qui deviennent alors pathogènes ;

- passer dans le circuit artériel, même si leur nombre est relativement faible, par exemple lors d’une manoeuvre de Valsalva au palier en cas d’existence d’un FOP.

Les signes dépendent de la localisation des bulles pathogènes.

Si les risques sont relativement faibles, les études (FFESSM et DAN) montrent que 75 % à 90 % des ADD surviennent malgré le respect des procédures.

Cela signifie que l’amélioration constante des modèles permet de bénéficier désormais d’une désaturation sûre, mais que les cas qui persistent se situent majoritairement en dehors du domaine de validité des protocoles (ordinateur, tables).

Pour plonger en sécurité, il faut donc non seulement :

1) respecter un protocole de désaturation ;

mais également prendre en compte :

2) l’existence de facteurs individuels de risque ;

3) les profils de plongée dangereux ;

4) les comportements à risque.

Plus la quantité d’azote accumulée est importante, plus la probabilité de risque d’ADD augmente. Les principaux facteurs à prendre en compte sont :

- Le temps de plongée.

- La profondeur.

- La consommation d’air. Effort, froid, essoufflement, stress augmentent cette consommation et donc le niveau de saturation en azote. De plus, certains individus consomment plus d’air que d’autres ou éliminent moins bien l’azote lors de la désaturation (efficacité du filtre pulmonaire).

Julien Hugon, dans sa thèse soutenue en 2010 à Marseille sur la Modélisation biophysique de la décompression, résume parfaitement la situation : « Le fait de pratiquer des efforts lors d’une exposition augmente le risque de générer un accident de décompression (Vann et Thalmann 1993). Ceci tient au fait qu’une activation de la circulation augmente la vitesse de saturation de certains tissus (muscles squelettiques, peau, tendons…). Aussi, pour un même type d’exposition, la quantité de gaz que l’on peut dissoudre dans l’organisme peut être nettement supérieure si des exercices sont pratiqués, ce en comparaison d’une situation au repos. Pour se prémunir contre l’accident de décompression de manière efficace, les durées des décompressions doivent alors être majorées (Vann et Thalmann 1993) ». - Sont également à considérer :

- L’intervalle de surface entre deux plongées. Plus il est court, moins l’organisme a le temps d’éliminer l’azote en excès issu de la précédente plongée.

- Le nombre de plongées réalisées dans la journée, sur la semaine…

Tout plongeur doit avoir à l’esprit que son niveau de saturation en azote et donc le risque d’ADD dépendent non seulement de la profondeur et du temps de plongée, mais également de la consommation d’air et des réactions de l’organisme. Si les modèles de désaturation sont fiables, ils ne peuvent pas pour autant offrir une garantie absolue à 100 % des plongeurs dans 100 % des plongées. Il ne faut donc pas faire une confiance aveugle à un ordinateur ou à des tables de désaturation.

Les facteurs individuels de risque sont des facteurs favorisant les risques ADD. Par définition, ils ne sont pas pris en compte par les modèles de désaturation car non généralisables. À titre d’illustration, en voici une liste inspirée librement de celle de la Comex et qui ne l’engage pas :

- Mauvaise forme physique, longs trajets pour aller plonger, manque de sommeil, fatigue excessive y compris sur le plan psychique : stress au travail, problèmes familiaux ou professionnels durables, perte d’emploi, situation de divorce, etc. ;

- Mauvaise hygiène de vie : tabac (cela augmenterait la viscosité sanguine par 3 ou 4 , alcool, nourriture trop riche…) ;

- Âge > 40 ans ;

- Poids ;

- Antécédent de maladie grave, prise régulière de médicaments ;

- Manque de pratique récente : plongées précédentes remontant à plusieurs semaines. Pour les plongeurs de loisir français de Métropole, le cas typique est celui des plongées du mois de mai, à l’ouverture de la saison. C’est la période où le CROSS constate le plus d’accidents graves de plongée car de nombreux plongeurs sédentaires durant l’hiver, plutôt que de prévoir une phase de réadaptat ion progressive à la

profondeur, en profitent pour plonger à la limite de leurs prérogatives. Le bon sens voudrait pourtant que l’on soit prudent et qu’après une interruption de quelques semaines ou mois, on reprenne l’activité progressivement, à l’image de ce qui se pratique en alpinisme ou en aéronautisme par exemple. Profil à risque : 50 ans, 50 m, plongeur aguerri.

Selon que vous cumulez 2, 3, 4, ou plus de ces facteurs favorisants, il vous faut :

- limiter la profondeur (ex. 20 m) ;

- limiter le temps de plongée ;

- utiliser du nitrox ;

- respecter un intervalle entre deux plongées d’au moins 3 à 4 h ;

- accroître les paliers (par exemple en utilisant le mode « personnalisation » de votre ordinateur) ;

- ne faire qu’une plongée par jour ;

- voire même renoncer temporairement à plonger lorsque trop de facteurs sont réunis.

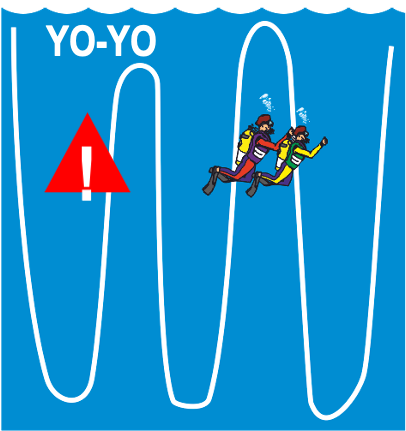

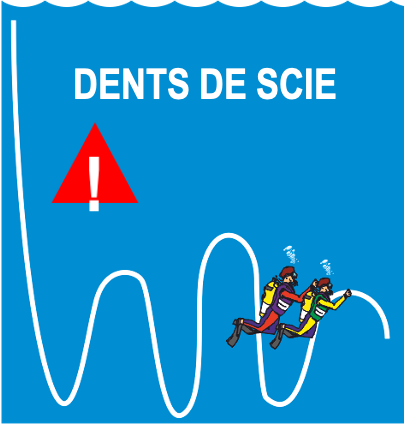

Remontées rapides, yo-yo et dents de scie provoquent la création de bulles et augmentent les risques d’accidents de désaturation. Ces profils sont dangereux par nature et ne sont pas pris en compte par les modèles de désaturation (et ne sont donc pas pris en compte par les ordinateurs de plongée).

Il est aujourd’hui avéré que certains profils de plongée comportent des risques, par l’augmentation du

nombre de bulles qu’ils occasionnent.

Ce sont :

- Les remontées rapides.

- Les plongées « yo-yo » ou en « dents de scie » (même si la vitesse de remontée est lente), une remontée de 10 m (1 bar de variation de pression, indépendamment de la profondeur) étant suffisante pour créer des bulles dont les effets physiologiques ne sont pas neutralisés par une redescente.

- Les plongées consécutives, et les plongées successives rapprochées. L’étude de DAN Europe sur le sujet a montré que la quantité de bulles détectables par effet Doppler était près de deux fois plus importante dans le cadre de plongées successives que pour des plongées unitaires. Afin de limiter ce phénomène, il est recommandé de respecter un délai d’au moins 3 ou 4 heures entre deux plongées.

Consulter la Fiche Info Plongée Plaisir sur le sujet.

Le cas des profils inversés est plus controversé. Lors d’une plongée simple, cela consiste à atteindre la plus grande profondeur en fin de plongée, puis à remonter en surface (exemple, plongée le long d’un tombant). En plongée successive, cela revient à descendre plus profond que lors de la première plongée. Hamilton et Thalmann indiquent à ce sujet : aucune preuve convaincante n’a montré que les profils inversés en plongée sans décompression entraînent une augmentation des risques d’accidents de décompression […] pour les plongées sans décompression à moins de 40 mèt res et dont le différentiel de profondeur est inférieur à 12 mètres.

La dangerosité de ce type de profil dépend donc de la profondeur, du temps de plongée et de la différence de profondeur entre les deux plongées.

En l’absence de certitudes sur ce point, nous ne saurions trop recommander aux directeurs de plongée et aux guides de palanquées de rester prudents.

Au-delà du respect des procédures et profils de plongée corrects, le comportement individuel est aussi un élément clef de la prévention des accidents.

Voici quelques règles de bonne pratique :

- Éviter les hyperpressions thoraciques, elles peuvent provoquer l’ouverture de shunts cardiaque (foramen ovale perméable) ou pulmonaires, ce qui autorise le passage de bulles veineuses dans le circuit artériel. Il faut donc proscrire les manoeuvres de Valsalva à la remontée ou au palier, ainsi que les efforts violent (exemple, relever une ancre à la main, remonter une bouteille en force à bord d’un pneumatique…).

- Éviter de faire du sport, et de manière générale, tout effort violent (exemple, remonter un mouillage conséquent), dans les 2 heures qui suivent une plongée. Dans un organisme sursaturé en azote, cela ne peut que favoriser la création de bulles.

- Éviter aussi de pratiquer de l’apnée moins de 6 heures après une plongée en scaphandre. Cela entrave l’élimination naturelle de l’azote, avec des conséquences non mesurées sur les plongées successives. De plus, les multiples phases de descentes et remontées, souvent rapides, augmentent les risques d’apparition de bulles.

- Monter en altitude ou prendre l’avion après une plongée peut favoriser l’apparition d’un accident de désaturation (voir Fiche Info Avion, altitude et plongée).

- Généralement, il est conseillé de ne pas effectuer plus de 2 plongées par 24 heures, avec une pause tous les 6 ou 7 jours. Cependant, l’utilisation désormais très répandue des ordinateurs et le développement du tourisme sur de courtes périodes (1 à 2 semaines) font que les pratiquants souhaitent plonger 3 ou 4 fois par jour, afin de profiter pleinement de leurs vacances.

Face à cette réalité, rappelons qu’un ordinateur calcule un profil de désaturation à partir d’un modèle mathématique valable pour 2 plongées par 24 h, successives ou non. Au-delà, un ordinateur effectue tout de même les calculs mais rien n’indique actuellement que les données affichées sont fiables. Dans ces conditions, l’emploi d’un ordinateur ne dispense pas de respecter la « règle des 2 plongées par jour » … ou de prendre ses responsabilités.

Vidéo

Voir également la vidéo sur la reprise progressive de la plongée.

© Extrait des livres Plongée Plaisir par Alain Foret aux Editions GAP.

Toute reproduction interdite sur quelque support que ce soit sans accord écrit de l’éditeur et de l’auteur.