INFO SHEETS > INITIATE YOU

Hand signals

It's curious, among divers, this need to make sentences with the handss!

Paraphrase freely inspired by the dialogues of Jacques Audiard inTontons Flingueurs.

In the world of silence (which is the world without speech, not the world without noise), communication between divers is an element of safety essential. The relevance of the signs takes precedence over their number.

Hand signals

Simple to be effective: safety first

From the origin of the creation of diving signs (1958), the following principles were established:

1. Few signs of diving, in order to focus on the essentials, safety.

2. Eviter des nuances inutiles qui pourraient conduire à des incompréhensions et augmenter les risques d’accidents (ex. “Ok, Tout va bien” ou “Ça ne va pas, une assistance est requise”, inutile de prévoir un signe entre ces deux situations).

3. Be able to perform the signs with one hand in order to take into account all possible situations.

Okay, are you okay?

Ok, everything is fine*.

Ok area*

Surface distress*

OK at night*

Ok at night on the surface*

Night Surface Distress*

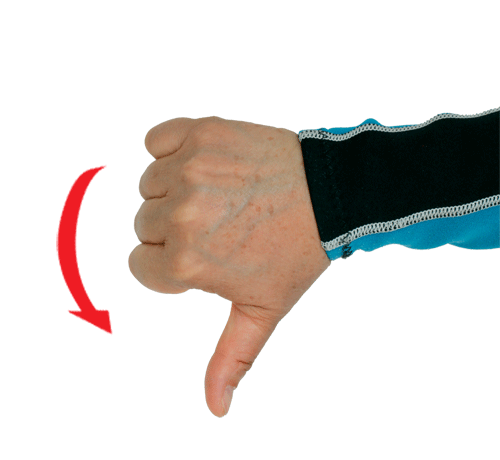

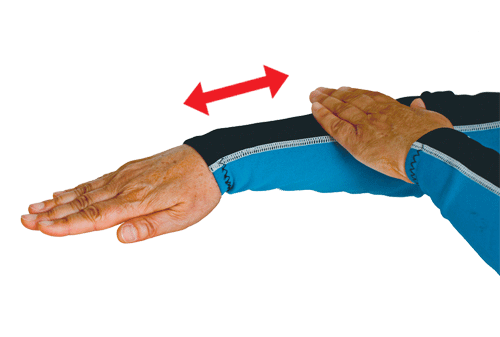

It's not ok*

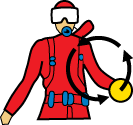

We are going down*

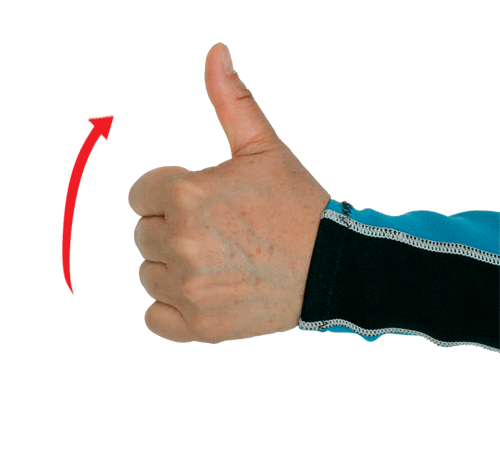

We go up*

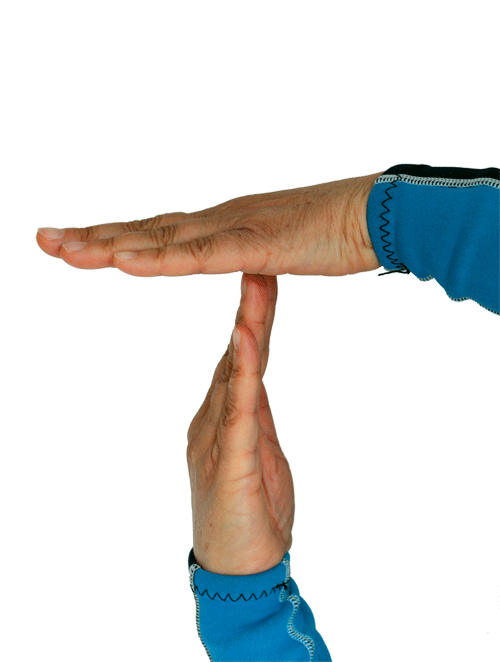

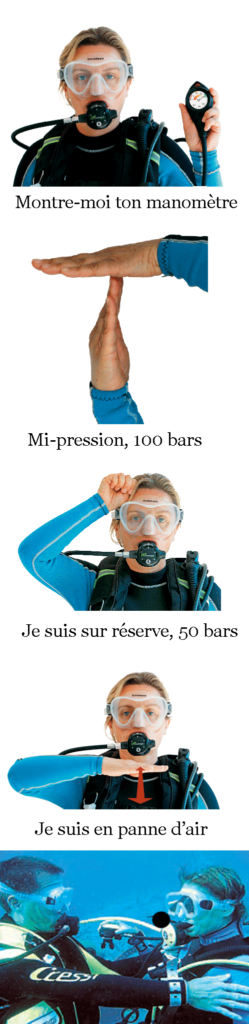

Show me your manometer

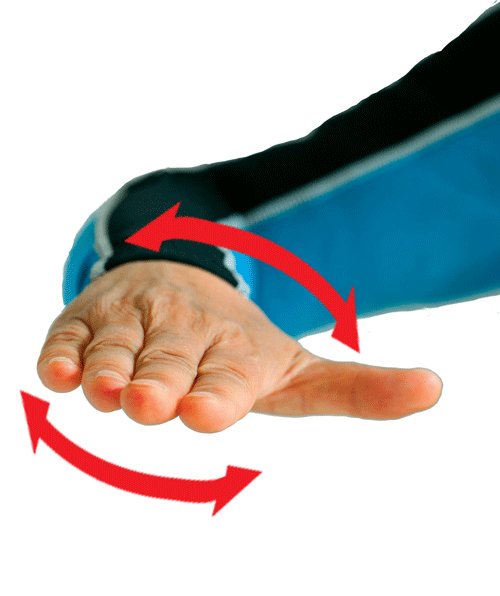

Half Pressure (100 bar)*

I am on reserve (50 bars)*

I'm out of air*

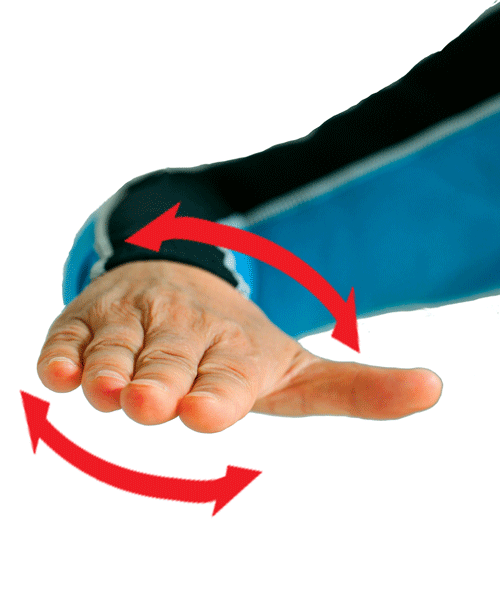

I'm out of breath

Breathe out, exhale

I'm cold

stabilize yourself

End of year

End of dive

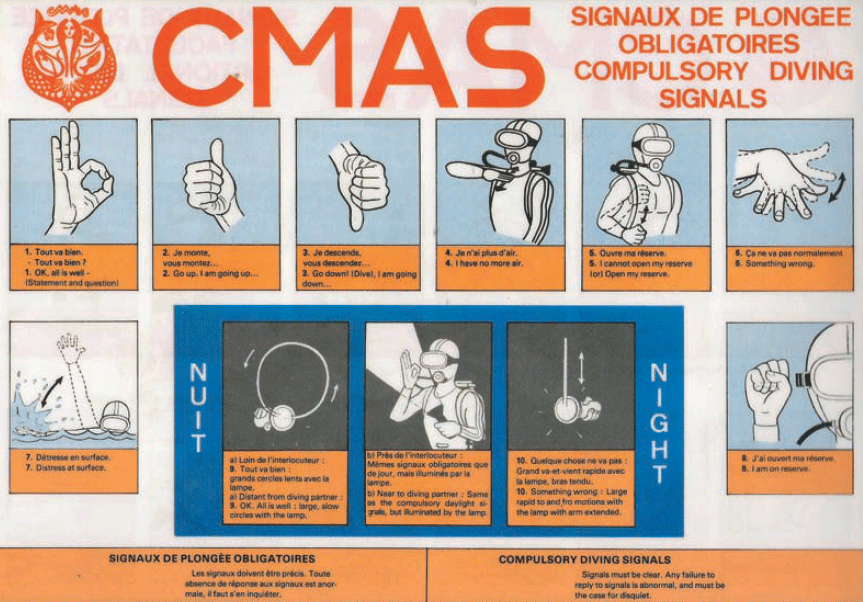

* Signs standardized by CMAS (Congress of Barcelona 1960 and Singapore 1999)

OK, EVERYTHING IS OK

This sign is both a question "Are you okay?" and a response “Ok, everything is fine”.

When your instructor or your dive guide gives you this sign, you must answer either "Ok, everything is fine" or "It's not fine" by possibly pointing out what is wrong. For example by showing your ear, if you have a problem balancing the pressures on the descent. A non-answer to the question "Is everything okay?" is equivalent to “It's not going well” and induces an action from the instructor or the dive guide.

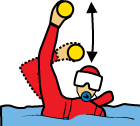

OK, EVERYTHING IS OK: ON YOUR ARRIVAL ON THE SURFACE

Par défaut, lors de l’arrivée en surface, l’absence de signe “Ok, tout va bien” conduit à déclencher une procédure d’urgence.

IT'S NOT OK

Sign "It's not okayto do as soon as something important goes wrong.

Depending on the context, a team member, the dive guide or the diving instructor will immediately assist you.

Most often this will end the dive.

ENSURE AIR RESERVES

Throughout your dive, you should check your pressure gauge for available air reserves (however, avoid doing this too often unnecessarily).

From time to time, your instructor may ask you "Show me your manometer".

Then just turn the dial of your manometer (or your dive computer if it incorporates air management) towards him so that he can read the remaining pressure.

Wanting to indicate the pressure by diving signs symbolizing a number is useless, a source of confusion and a waste of time.

In all cases, indicate100 bar, half pressure», as soon as the needle of your pressure gauge indicates 100 bars.

In order to avoid any complications, do not take into account the initial pressure of the bottle (180, 200 or 220 bars) to calculate the half-pressure, make the sign "half-pressure" from 100 bars.

Generally, your instructor or your dive guide will take this into account and ensure that you are out of the water with 50 bars in reserve. If this is not the case, then remember to indicate "I'm on reserve» as soon as your pressure gauge indicates 50 bars (red area of the dial).

Following these instructions will prevent you from being confronted with the "air failure», always stressful although managing perfectly if you stay close to your dive guide throughout the dive: this one will then make you breathe on his emergency regulator and will end the dive for the whole dive .

AVOID FALLING OUT OF BREATH

To avoid getting out of breath, keep in good physical shape, avoid heavy meals before diving and do not dive if you are tired (long trip, lack of sleep, etc.).

During the dive, avoid efforts that are too great for you and, in any case, get into the habit of practicing deep voluntary exhalations as soon as you make an effort, even a slight one.

If the preventive measures are insufficient, at the first signs (feeling of slight suffocation, inability to hold a “control pane”), give the sign “I am out of breath” to your dive guide. He will ask you to stop all effort, calm down and force the exhalation.

This usually signals the “end of the dive”.

I'M COLD

To avoid getting cold, eat properly before diving, cover up if necessary (if you are cold on the surface it can only get worse underwater) and wear a fitted and sufficiently thick wetsuit.

If that's not enough, make the "I'm cold" sign right away. This will end the dive for the entire dive.

Des informations du type “J’ai un peu froid”, “J’ai moyennement froid”, ne sont d’aucun intérêt. C’est un signe binaire, lorsque vous le faite, c’est que vous avez vraiment froid et qu’il faut mettre fin à la plongée.

A little history …

The need to have standardized signs became apparent very early on, from the symposium of March 8, 1958 in Cannes (report published in October).

Statement by Pr. Jacques Chouteau, President of the first international colloquium on the teaching of diving (1958)

For group diving (the only one to be recommended), a simple means of communication, allowing mutual understanding of a few elements of the situation, is an essential safety factor.

Many signs have been proposed, moreover in an unsystematic way. Their multiplicity, in addition to the difficulties of understanding between divers from different clubs, can become catastrophic if these signs have opposite meanings for the partners.

It is to remedy this state of affairs that the Federation offers a set of reduced and simple signs, which we wish to see generalized.

Note that these were chosen after careful consideration and practical experimentation. The proposed signs are essentially safety signs allowing a diver to signal to another diver with one hand. (…)

During the 1958 conference, these signals were discussed and the majority of participants decided to adopt them despite the differences between this code and that of the Anglo-Saxons. They did, however, make a very interesting suggestion regarding the need for a surface signal. We have

therefore proposed and partly adopted the following convention: on arrival at the surface, far from the surveillance boat or the coast (if the dive is carried out from this point), the emerging diver at ease manifests his state by a signal “Everything is fine”: arm extended, kept vertical, the hand making the sign “everything is fine” (circle with the thumb and the index), this for 5 to 10 seconds.

The absence of a sign from the diver appearing on the surface must be considered as the fact of an impossibility to report his condition and help must be brought to him.

Discomfort, difficulty reaching shore, or distress are signaled, as in diving, by the rhythmic or disorderly flailing of the arms above the surface. It should be noted that in the event of accidental drowning on the surface, these are the innate gestures, their nuances will signal to the observer the degree of gravity of the situation.

The British have criticized this convention by offering different signs for "mild" or "severe" distress. Experience shows that this distinction is illusory, one quickly transforming into the other. The doctrine of the federation is “it's going well” or “it's not going well” and we think that's wisdom. Better to bother for nothing, than not to bother for an incident that could become serious.”

En 1960, lors du congrès de la CMAS à Barcelone, ces signes inspirèrent grandement ceux adoptés par la CMAS. Yves Normand réalisa les planches officielles qui constituèrent la première publication de signes de plongées normalisés sur le plan mondial. Il furent complétés en 1999 lors du congrès de Singapour (signe “mi-pression, 100 bars”).

The signs today

The tendency towards inflation in the number of diving signs, already present when they were officially created in 1958, is still debated. Some books publish dozens or even hundreds of diving signs. This seems to us to pervert the logic of diving signs, which must remain essentially focused on safety and therefore be frank, unambiguous and few in number for perfect memorization.